On the morning of 28 May 1918 troops belonging to the American Expeditionary Force’s 1st Division embarked on the first full US-led offensive of the First World War at Cantigny in northern France. Although the assault was a limited one, and of comparatively minor significance in overall strategic terms for the Allies, its success was an important psychological boost for Pershing’s forces. Patrick Gregory reports.

The First Division had been in the line for a month already in the Montdidier sector in northern France when their moment came at Cantigny.

America’s commander on the Western Front, General John Pershing, and these, his most trusted troops of the ‘Big Red One’, led by General Robert Lee Bullard, were keen to see action. They wanted to test themselves in battle; but it was also an opportunity for Pershing to bite back – or so he hoped – at some of the criticism he felt had come his and his troops’ way from Allied leaders.

Having borne the brunt of two German offensives already in the preceding months – Operations Michael and Georgette – the Allies initially thought that a further enemy attack was in the offing closer to the coast, above the 1st’s present position. A pre-emptive move by the division in the north of their sector might help distract German forces there, providing them with a substantial role in the present fighting.

General Robert Lee Bullard (Photo: Library of Congress, George Grantham Bain Collection)

But when intelligence reports indicated that that was not, after all, on the cards, a decision was taken in conjunction with Bullard’s French commander, Eugène Debeney of the First Army, to opt for a more limited operation. The plan was to iron out a bulge in the sector some 20 miles south of Amiens, and only four miles’ distance from Montdidier itself. At the tip of this bulge or salient lay the small village of Cantigny.

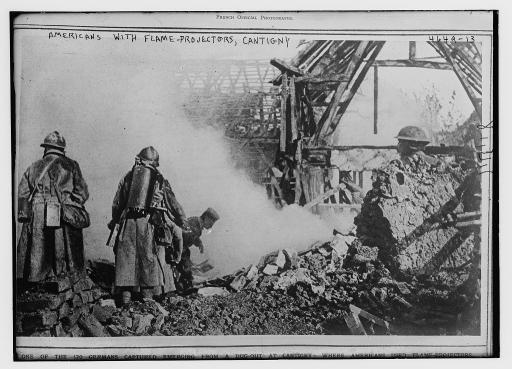

The strip of land to be attacked was narrow, so a plan was worked on to attack frontally with just one regiment of the division, the 28th Infantry. It was led by Colonel Hanson Ely, an imposing and uncompromising figure, and one who demanded the most from his men. Ely spent the week prior to the attack putting the soldiers through their paces, training them in the craft of advancing behind a rolling barrage, with a lead platoon of men using flamethrowers. Tactics called on the men to secure their target quickly and to prepare for the certain concerted enemy response when it came.

French support

To aid the operation the Americans were afforded a substantial array of French artillery pieces, several hundred in number, including larger 280mm guns. To these were added a dozen tanks, a consignment of French planes for observation support and the flamethrower teams. With the date now set for 28 May, Ely’s troops began to take up their positions the day before. But just as they did so, news began to filter through of another major German assault, beginning some 50 miles to the south east of them over the ridge of the Chemin des Dames. That offensive was driving further south.

It presented the French and their American allies with a choice: to stick or twist? Proceed with their comparatively minor assault or move to the lines which had now been breached? The decision was taken to go ahead, albeit with a reduced – and, over time, steadily reducing – arsenal of artillery at their disposal.

Attacking at Cantigny – 28th Infantry Regiment, supported by the French 5th Tank Battalion (Photo © IWM Q 102930)

At 5.45 on the morning of 28 May, after a preliminary salvo of smaller fire, the heavy guns opened up. Around an hour later Ely’s troops began to move. His regiment’s three battalions, one abreast of the other, moved from west to east, bearing down on the salient. The 1st battalion moved south of the village, supported by a separate battalion of the nearby 26th regiment. The 2nd battalion of Ely’s men concentrated on fighting its way into the village itself and the 3rd battalion swept north. Within the hour they had covered the 1,500 yards necessary into and around Cantigny. Ely could report: ‘Nearly all of objective reached. Everything going fine.’

The units’ next task was to secure the area beyond the village – specifically points on the ridge behind. It was important to bed down in preparation for the expected German counter attack, an onslaught which was not long in coming.

By mid-afternoon heavy German shelling was pounding American positions. The big artillery pieces afforded the AEF troops at the outset of the attack were now being moved south-east to beef up defences breached by Ludendorff’s latest offensive. Two of the 28th’s battalions were now falling back in the face of the barrage unleashed against them.

Counterattacks

The pounding and counterattacks continued over the next three days, two German assaults coming in quick succession on 29 May. What had started off as an easy and early success was quickly becoming a protracted defence of the village and its surrounds. But the Americans’ light and medium artillery stuck tenaciously to its task, thwarting each incursion as it came.

German attempts to recapture Cantigny finally ceased on 30 May. That night, men of the 16th Infantry, who had been held in reserve, relieved the exhausted and depleted battalions of the 28th. Some 200 of their officers and men had been killed or were missing and nearly 700 wounded.

George Marshall, later Chief of Staff of the US Army, who had cut his teeth as a strategist planning the assault, later admitted that the losses suffered were not ‘justified by the importance of the position itself.’ But what was less in doubt was that the 1st Division’s men had shown themselves well on the battlefield. A relieved Robert Lee Bullard, while acknowledging that more important battles had preceded it and would soon follow, said that Cantigny had the effect of heartening friend and disheartening foe: ‘It was a demonstration to the world of what was to be expected of the Americans.’

Marne threat

However, of more serious and immediate concern to Allied commanders was what was unfolding to the south-east. Seventeen German divisions had swarmed over the Chemin des Dames and the river Aisne. By the first night they had reached the river Vesle 12 miles further south and Ludendorff now decided to press on towards the river Marne and the strategic bridgehead there of Chateau-Thierry. If captured, Paris would once more be in German sights, little more than 50 miles distant. It would be there that other American Forces of the AEF’s 2nd and 3rd divisions would soon be tested.

Somme American Cemetery, near St Quentin – last resting place for some of those who fought at Cantigny (Photo: Centenary News)

Patrick Gregory is co-author with Elizabeth Nurser of ‘An American on the Western Front: The First World War Letters of Arthur Clifford Kimber 1917-18’ (The History Press) American on the Western Front @AmericanOnTheWF.

Images courtesy of Library of Congress, George Grantham Bain Collection: LC-B2-4649-13 (flame-throwers), LC-B2-5062-8 (Robert Lee Bullard)

Imperial War Museums, © IWM Q 102930 (US 28th Infantry)

Centenary News (Somme American Cemetery)

© Patrick Gregory and Centenary News

Posted by: CN Editorial Team